That would be Envy (although I would put in a good, or bad, word for Sloth, my bete noire). The envious man is purely destructive; he wishes only to take away what the man he envies has, not to possess it himself. He neither seeks nor takes solace in company. The emotion is almost universal, yet rarely acknowledged. In fact in English we tend to use the German term Schadenfreude (literally, “joy in misery”), reserving “envy” to mean mere covetousness, like wishing you had a car as nice as your neighbor’s.

Jim at Philosoblog has some excellent thoughts on the way envy underpins leftist politics. Having read Helmut Schoeck’s definitive work on the subject, I have one point to add. Appeasing envy is a losing strategy because envy is implacable: it can be kindled by any inequality, no matter how small; any difference, no matter how slight. Envy-avoidance is magnanimous. This, being another quality to envy, makes matters worse.

Envy is generally directed at those with just a little more, whose circumstances are easy to imagine. The most envious societies in the world are poor tribes like the Maori of New Zealand where no one has anything at all. Schoeck’s description of the institution of muru is instructive.

The Maori word muru literally means to plunder, more specifically, to plunder the property of those who have somehow transgressed in the eyes of the community. This might be seen as unobjectionable in a society with no judicial apparatus. But a list of the “crimes against society” which were visited with muru attack might give pause for reflection. A man with property worth looting by the community could be certain of muru, even if the real culprit was one of his most distant relatives. [The parallel to modern liability law is almost too obvious to mention.] …If a Maori had an accident by which he was temporarily incapacitated, he suffered muru. Basically, any deviation from the daily norm, any expression of individuality, even through an accident, was sufficient occasion for the community to set upon an individual and his personal property….

The muru attackers sometimes converged upon the victim from a distance of a mile; it was attack with robbery by members of the tribe who, with savage howls, carried off everything that was in any way desirable, even digging up the root crops….

In practice the institution of muru meant that no one could ever count on keeping any movable property, so that there could be no incentive to work for anything. No resistance was ever offered in the case of a muru attack. This would not only have involved physical injury but, even worse, would have meant exclusion from taking part in any future muru attack. So it was better to submit to robbery by the community, in the hope of participating oneself in the next attack. The final result was that most movable property — a boat, for example — would circulate from one man to the next, and ultimately become public property.

Could it be, perhaps, that a citizen today in an exceptionally egalitarian democracy, when submitting without protest to a very tiresome and high tax rate, secretly hopes that, like the Maori, some special government scheme might enable him in some way to dip his hand into the pocket of someone better off than himself?

Lest you think Schoeck is extrapolating idly, I give you Richard Cohen. Have a look at this and tell me the man wouldn’t enjoy a bracing muru raid.

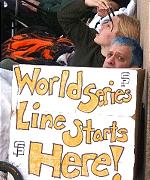

You know those idiots you see waiting in long lines to get into Star Wars movies and rock concerts and sporting events? Well maybe you don’t, but I do! My friend Michael Krantz, an occasional God of the Machine

You know those idiots you see waiting in long lines to get into Star Wars movies and rock concerts and sporting events? Well maybe you don’t, but I do! My friend Michael Krantz, an occasional God of the Machine